This all started one evening of April, 1971 when a maverick politician from Uttar Pradesh met one meritorious lawyer of Allahabad High Court. The story is full of all the elements required to make it a compelling read.

It has intrigue, espionage, machinations, emotions, greed, ambition, drama, judicial valour and compromise both, subversion, victimization etcetera etcetera.

The politician had recently lost the Lok Sabha election against the then Prime Minister of the country. He was dead sure that he would have won but for chemical treatment of ballot papers. His charge, like many from the opposition parties in that general election, was that at the behest of the ruling party of the Centre at the time of the printing of the ballot papers some chemical treatment had been done so that tick mark in favour of any other candidate except Congress would vanish and a tick mark would appear automatically against the name of the Congress candidate as if vote was originally cast in his favour.

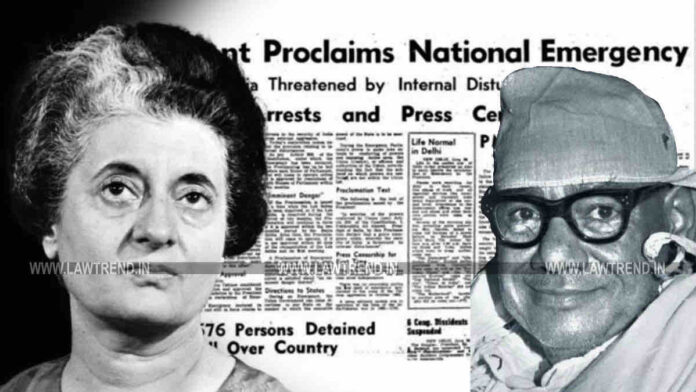

This write up is about ‘the’ election petition namely ‘Raj Narain Vs. Indira Gandhi’ and its unintended consequence – the Emergency. As a citizen and as a student of law, we must constantly remind ourselves the darkest phase of democracy in free Bharat, called Emergency, so that we as nation may remain ever vigilant to any possible future onslaught to our hard earned democratic freedom.

Raj Narain instructed his lawyer Shanti Bhushan to challenge the election of Mrs. Indira Gandhi from Rae Bareli Lok Sabha constituency. The result was declared on March 9th ,1971. According to him, other grounds apart, the main plank of attack should be the chemical treatment of ballot papers. He strongly believed that electoral process has been subverted due to chemical treatment of ballot papers. Shanti Bhushan, however, did not much like the idea. According to him, this did not sound a good ground for a serious election petition. Both of them worked on a few more serious grounds and on a thorough scrutiny, did find a few, in fact; however, Raj Narain stuck to his original charge of chemical treatment of ballot papers and prevailed upon Shanti Bhushan to include this charge too in the election petition.

The charges now in final shape contained in the petition against Mrs. Indira Gandhi, apart from chemical treatment of ballot papers, were like procuring the assistance of Yash Pal Kapoor for her electioneering while he was still a gazette officer, use of Air Force planes by her for her election meetings, getting the local administration of Rae Bareli under District Magistrate (DM) & Superintendent of Police (SP) to erect barricades, construct rostrums and arrange loud speakers for her election meetings, alluring the voters by distributing liquor, quilts, blankets etc. and hiring vehicles for their free conveyance to and fro polling booths, bribing one Adwaitanand to contest election from Rae Bareli, appealing religious sentiments of voters by using the election symbol of a cow and calf and also violating the prescribed limit of election expenditure. Under the Representation of the People Act, 1951, these charges constituted corrupt practices and hence, the petition sought that the election of Mrs. Gandhi be declared void. The election petition, eventually, came to be filed on last day of the limitation period on April 24th, 1971 in Allahabad High Court.

Also Read

Mrs. Gandhi filed her reply to the election petition and rubbished all the allegations. As explanation, she said that Yash Pal Kapoor did not do any electioneering for her before resigning. In other words, he first resigned from his post and then took up the election work for her. Also that she travelled in Air Force planes as per the standing instructions of the Govt. of India which planes were used to make available to a Prime Minister as per his or her travel arrangements even for non official purposes. Further that the erection of barricades, construction of rostrums etc. were done by the local administration only for law and order purposes and not for electioneering in her favour. And that cow and calf was not religious symbol.

Issues for trial were framed, thereafter, on all charges; however, not as regards chemical treatment of ballot papers. In fact, Shanti Bhushan had suggested the Judge namely Justice Broom who was hearing the petition at that stage to look for himself a few ballot papers cast in favour of his client as well as the opp. party and give his finding if actually any tampering by chemical treatment had taken place. The Judge examined the ballot papers calling for a few bundles and concluded that there was no tampering by chemical treatment. Shanti Bhushan did not press and hence no issues were framed on this score. Raj Narain was not amused, of course. The charge with which he was too convinced as a substantial ground for his election petition, did not find favour with the Court. This is not unusual in Courts. Many a times, final outcome of a case is much beyond what a lawyer had initially thought of while accepting the brief and what a client had imagined. This is in fact what had happened in this case also. Cases do evolve after they are filed in Courts. However, sometimes, to unwanted results as well. We’ll see in this story also as it unfolds.

The election petition was now headed for serious court battle. Senior Advocate S C Khare represented Mrs. Gandhi. He sought deletion of a few issues since the facts pleaded in the petition lacked, what is called in election laws jargon, the material particulars as regards charge of procuring assistance of Yashpal Kapoor and bribery to Adwaitanand. The Judge agreed and deleted the two issues concerning. Round one was in favor of Mrs. Gandhi.

To shore up the charges of Mrs Gandhi having procured assistance of a gazette officer, Shanti Bhushan filed amendment application and sought to clearly mention in the election petition that Mrs. Gandhi held herself out as candidate since December 27th, 1970 when the Lok Sabha was dissolved and Yashpal Kapoor started working her election ever since then. He chose not to press the bribery charges. Khare opposed the application. The Judge agreed with Khare. Khare again carried the day. Amendment was refused. Round two was also in favour of Mrs Gandhi, temporarily though.

The order of the High Court was challenged by Raj Narain in Supreme Court. A Bench comprising Justice K S Hegde, Justice Jagan Mohan Reddy and Justice K K Mathew set aside the High Court’s order and restored the issues albeit now recast in a different manner. Justice Hegde, who authored the judgment, also did not uphold the conclusion of Justice Broom that Yashpal Kapoor ceased to be in government employment from January 14th 1971 as he had resigned on a day earlier on January 13th. Justice Hegde observed that resignation may have been tendered on January 13th, since it was accepted only on January 25th and hence it can not be easily concluded that resignation was effective from January 14th with retrospective effect. He ordered for re examination of this point in view of the service conditions of Yashpal Kapoor. This judgment came on March 15th, 1972 {reported in (1972) 3 SCC 850}. This later on proved to an interesting twist with cascading effect.

It is apt to recall at this juncture that political executive of the country and the Supreme Court right from late 1970s had locked their horns in a number of cases starting from Golakh Nath in 1967, RC Cooper-Bank Nationalisation case in February, 1970 and Madhav Rao Jivaji Rao- privy purse case in December, 1970. Some call it the struggle for supremacy over Constitution. Though, it finally came to be settled in Kesavananda Bharati case, however, great mutual frustration persisted even thereafter. It was in this larger background that this election petition against the head of the political executive- the Prime Minister, was also slowly brewing up in Allahabad High Court.

The judgment in Kesavananda Bharati case was delivered on April, 24th 1973. And almost simultaneously in Allahabad High Court, based on Supreme Court’s order, three additional issues was framed on April 27th, 1973 in the election petition. In some uncanny way, Keshavananda Bharati and “the” election petition were to cross each others path in future.

All three additional issues, in sum and substance, were like if Mrs. Gandhi held herself out as candidate even before she filed her nomination on February 1st, 1971; if Yashpal Kapoor continued in government employment even after January 14th, 1971 when he tendered his resignation and till which date; and finally if Mrs Gandhi procured assistance of Yashpal Kapoor for her electioneering while he was still in Govt. employment.

The Basic Structure Doctrine (BSD) which came to be settled in Kesavananda Bharati case as putting limitations on the amending power of the Parliament was not taken kindly by the then Central Govt. led by Mrs. Gandhi. Three senior most Judges who had held in favor of the doctrine were superseded and their junior one who gave judgment against the doctrine namely Justice A N Ray was appointed the CJI. One of the three superseded Judges, was Justice Hegde. Interestingly, Justice Hegde admitted in an interview that he was superseded because of the judgment he gave in the election petition against Mrs. Gandhi.

After issues in the election petition were settled, the case was put up for trial in September, 1973. Oral examination of petitioner’s witnesses started. The petitioner summoned one state govt. servant to produce the confidential Blue Book and certain other documents. Blue Book contained detailed instructions as regards protection of the Prime Minister during tour or travel. The State Govt. claimed privilege under Evidence Act and objected to produce the Blue Book and certain other correspondences exchanged between Central Govt. and State Govt. over the Police arrangements for the meeting of the Prime Minister. This document was required for the purposes of proving charges relating to use of local administration of Rae Bareli in election of Mrs. Gandhi. The Judge refused the claim of privilege and ordered for production of the documents. The matter was taken to Supreme Court by Mrs. Gandhi. The Supreme Court stayed the High Court’s order in April, 1974. Lawyers for both the sides, thereafter, sought joint adjournments in the High Court. The proceeding in election petition, hence, remained stuck up for some time pending disposal of privilege case by the Supreme Court.

The lawyers by this time had lost interest in the case as they hardly had expected anything to come of it, but democratic destiny of the nation had different plans, as proved to be true later on as the story developed further. Justice Srivastava retired meanwhile and now after summer vacation in July, 1974, the petition was taken up by Justice Jag Mohal Lal Sinha.

Justice Sinha had a reputation of an upright Judge. When the matter came up before him, he saw no point in keeping the matter just pending and instead asked the petitioner to produce evidences on other issues which were not connected with the claim of privilege or else the petitioner may drop all the charges. Asked point blank by the Judge, the petitioner felt compelled. He got recorded the evidences of all its witnesses by January, 1975.

One significant development took place, meanwhile. This had bearing on the case in the election petition against Mrs. Gandhi. The Supreme Court, in the case of Kanwar Lal Gupta Vs Amar Nath Chawla {reported in (1975) 3 SCC 646} interpreted the law of election expenses. This decision came on October 3rd, 1974. The effect of this ruling was that what ever expenditure was incurred by the Congress party in the election of Mrs. Gandhi would have to be accounted in her election expenses. This Supreme Court decision strengthened the case of the petitioner on election expenses against Mrs. Gandhi. However, again as the electoral law destiny of the nation would have it otherwise, to nullify the Supreme Courts ruling, the law of election expenditure in the Representation of the People Act, 1951 was changed retrospectively. First an Ordinance was promulgated which subsequently was enacted into a law on December, 21st 1974 {The Representation of People (Amendment) Act, 1974- No. 58 of 1974}. Now, as per the changed law, the expenditure in the election of a candidate by any person, including even the candidate’s sponsor political party, would not be included in the election expenses of the candidate. This law was made applicable even on pending election petitions. Charge of excess election expenses against Mrs Gandhi now reduced to mere rut. This was the very first in a series of many more subsequent interferences, as we would see while the story progresses, where law was wantonly tweaked just to suit the case of Mrs. Gandhi in the election petition.

The privilege issue which was pending in Supreme Court all this while was finally decided by the Constitution Bench on January 24th, 1975. {reported in (1975) 4 SCC 428}. As an off shoot to this election petition, the field of law was of course enriched with an important ruling by the Supreme Court on the issue of executive privilege under Evidence Act. The Supreme Court set aside the High Court’s judgment, though. The claim of privilege was directed to be decided a fresh. Justice Sinha, in the light of the observations of the Supreme Court’s decision, examined the documents himself and sustained claim of privilege on a few documents and refused as regards certain others, which were then admitted in evidence.

In the election petition, examination of respondent witnesses started in February, 1975. First, PN Haksar, the then Deputy Chairman of Planning Commission was examined on the issue of resignation of Yashpal Kapoor. Second, Yashpal Kapoor himself was examined. And lastly, Mrs Gandhi testified as witness. Her appearance, a sitting Prime Minister, as witness has its own unique interest quotient. But, not for this write up. Examination of respondent’s witnesses was complete by March, 1975.

The stage was now set for final arguments. The date fixed was April 21st, 1975. Raj Narain meanwhile challenged the Election Law amendment also by filing a writ petition in High Court. All these were heard together. While Shanti Bhushan argued for Raj Narain, S C Khare defended Mrs Gandhi. Attorney General Niren De appeared to defend the attack on Election Law Amendment. All were big guns in their own right. In fact, Mrs. Gandhi wanted Nani Palkhivala to appear for her, but Khare didn’t want to share the lime light with anyone. However, hardly any case of importance in the country in 1970s & 80s miss the lawyerly stamp of Palkhivala in some way or the other. So, Palkhivala did appear, but later on in Supreme Court, as we will just see in this narration.

Arguments were completed till last working day of summer recess, that is, May 23rd, 1975. Judgment was reserved. The verdict came on June 12th, 1975. Indira Gandhi lost the case. Her election declared void. Of the seven, she was found guilty on two charges of corrupt practices. Justice Sinha found her guilty of taking assistance of local administration of Rae Bareli as also central govt. gazette officer namely Yashpal Kapoor while he was still in service, for her election. He debarred her from holding any public office for six years. Challenge to amendment of electoral law was, however, dismissed. The judgment caused the earthquake. Tremors of this judicial earthquake are still felt in political circles even after nearly forty five years.

Its not that it was linear progression of an otherwise sundry case where lawyers labored to the best of their liability and the Judge decided judiciously. Beneath this, there was a lot many circuitous manoeuvrings to influence the course. There was subtle suggestion to win over the lawyer of the other side. Shanti Bhushan was sounded by none other than Niren De for the post of Additional Attorney General, which post, he said, could be created especially for him. Shanti Bhushan did not budge. Even Judge was not spared. The bait was laid even for the Judge by his own Chief Justice. While the case was progressing, the Chief Justice D S Mathur allured Justice Sinha for elevation to Supreme Court only if he decided in Mrs. Gandhi’s favour. Even after the judgment was reserved, Justice Sinha and his Private Secretary were spied upon by the Intelligence Bureau of the country to get a sense of the judgment under preparation. The intrigues didn’t end here. Another Chief Justice namely K B Asthana, at the behest of Indira Gandhi, asked Justice Sinha to delay pronouncement at least till July. Justice Sinha didn’t take kindly to such request. To avert any further possible interference, Justice Sinha hurriedly fixed the date for delivery of judgment. This is all about how the verdict came mid summer vacation.

The Supreme Court-Parliament tussle aside, even the political firmament of the country was least prepared to bear this. Indira Gandhi was facing huge problems from her political opponents . The judgment proved to be a shot in the opposition’s arm. She panicked.

Though Justice Sinha had granted twenty days conditional stay; however, the sitting PM, judicially unseated, lost the moral authority to rule. She hurriedly appealed to Supreme Court against the High Court’s order. Raj Narain also filed cross appeal in respect of five charges he had lost of the seven he had laid in the election petition.

Justice Krishna Iyer was the vacation Judge before whom appeal was to be heard for stay. It was at this juncture, Nani Palkhivala eventually appeared to defend Mrs. Gandhi in Supreme Court. Even this hearing was not bereft of attempted executive manoeuvring. On the eve of the hearing, H R Gokhale, the Law Minister, sought an appointment with Justice Krishna Iyer to discuss this very case. He was refused.

Justice Krishna Iyer fixed the hearing for June 23rd, 1975. It was Monday. He called it a virgin day in his own inimitable way. Palkhivala requested for absolute stay on the High Court’s judgment. He argued that it would be embarrassing for the country if it’s PM continued on the strength of a conditional stay. Shanti Bhushan objected to absolute stay. Hearing over, Justice Krishna Iyer fixed 3:45 PM next day June, 24th 1975 for delivery of order. The order did come at the appointed hour but in the form of conditional stay only. Justice Krishna Iyer stuck to the precedent in such matters. Mrs Gandhi was allowed to continue as PM sans any power to vote in Lok Sabha. It was a humiliation hard for her Gandhi to stomach. Already beleaguered as she was politically, in a fit, in the dead hours of June 25th, 1975, she plunged the country into Emergency. A most dreaded word in political lexicon of the country, ever since then. Entire political opposition was silenced to prison. Press censorship imposed. Right to move to Court for protection of fundamental rights suspended.

Everything now under her control but the pending election petition appeal still hung like Damocles sword over her neck. She now turned to face it; rather, to frustrate it.

The Supreme Court reopened after summer vacation on July 14th, 1975. The appeal was listed before the CJI’s court on that day. Mrs Gandhi would not have thought of a better court. Justice A N Ray, a hand picked CJI by her in 1973 over three of his seniors, was CJI then. Palkhivala had already returned Indira Gandhi’s brief as a protest to imposition of Emergency. She was represented by the then Advocate General of Haryana, Mr. Jagannath Kaushal. It was adjourned that day for four weeks on the request made on behalf of Shanti Bhushan. It came to be listed next on August 11th, 1975.

But the legal world was changed beyond recognition, by then. As it turned out subsequently, the lawyers and the Judges involved in the appeal both were left to flog the dead horse only. The appeal had become infructuous when it came up next for hearing, thanks to series of amendments in law unleashed by the Govt. of the day under Mrs. Gandhi. This is perhaps the only occasion in the history of Supreme Court that it was rendered devoid of deciding a case in a designed manner like this.

The period interregnum between July 14th to August, 11th, 1975 proved to be an era of the most outrageous onslaught on the concept of rule of law. With entire opposition in prison, the ruling Party shamelessly embarked upon twisting and tweaking each piece of law which came in Mrs. Gandhi’s way of a favorable result of election petition appeal and also in the way her decision to impose Emergency.

As a first, 38th Constitutional Amendment was enacted. By this, the satisfaction of President for imposing Emergency was made absolutely non justiciable on any ground what so ever, that too with retrospective effect. Though as smoke screen, certain other amendments were also made. The Courts were now deprived to look into the reasons which prompted the President to declared Emergency. The pending petitions, in which the Emergency was under challenge in Courts, became unfructuous.

Then came the Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 1975. It was this amendment which removed all the thorns in the flesh for Mrs Gandhi. All such provisions relating to corrupt practices of which she was found faulting with and of which she could be found fault with in pending cross appeal of Raj Narain, were amended, with retrospective effect.

The definition of corrupt practice was changed so that the act of local administration of Rae Bareli helping Indira Gandhi in her election was taken out of its purview. It was inserted by way of a proviso to the definition of corrupt practice that if a govt. servant in purported discharge of his official duty makes certain arrangements for any candidate, it shall not be taken to be a corrupt practice. An explanation was added to specifically redress the issue of resignation of Yashpal Kapoor. It said that the date mentioned in the official gazette to be as date of resignation of a gazette officer shall only be deemed to be date of his resignation. It sanctified the date of resignation of Yashpal Kapoor to be Januray 14th, 1971 even though the President had accepted it on January 25th. Justice Sinha had given finding in his judgment that Indira Gandhi held out as candidate on January 25th. So the charge that Yashpal Kapoor, a central govt. gazette officer, assisted the electioneering of Indira Gandhi stood nullified as in view of this legal fiction created by amendment he had already resigned. To double nullify this charge, the definition of candidate was changed. Now, a person could be legally called a candidate only after his nomination. Mrs Gandhi had filed here nomination on February 1st, 1971. So, in any case whatever Yashpal Kapoor did towards her election before the nomination can not now be called corrupt practice. She now stood absolved of all charges of corrupt practice, with retrospective effect.

The appeal reduced to infructuous now. But that was still not the end.

Indira Gandhi did not want to take chances. She did not believe the Supreme Court would accept the electoral laws amendment and would refrain to pronounce on merits of the appeal. Her over zealous Law Minister, H R Gokhale, piloted another constitutional amendment bill. This was aimed to take out the election dispute of Indira Gandhi from the jurisdiction of the Courts with retrospective effect. It declared, with retrospective effect, the election of Indira Gandhi valid and the High Court’s judgment void. This 39th Constitutional Amendment was enacted within record four days. Lok Sabha passed it on August 7th , 1975 followed by Rajya Sabha on 8th . It was ratified by Congress ruled seventeen States on 9th. The President gave its assent on 10th. Now, as per this amendment, the pending election petition appeal was to be decided not by the Supreme Court, any more. It became double infructuous, now.

To further avert any possible chance of judicial scrutiny of the amendments, entire Representation of the People Act, 1951 along with both its Indira Gandhi induced amendments of 1974 and 1975, were put in Ninth Schedule of the Constitution. The fate of pending appeal was completely sealed now.

As even this perhaps did not satisfy the panicky Indira Gandhi. Authoritarian streak in her was in full flow. This time Law Minister Gokhale pulled almost as rabbit out of hat. On the last working day, August 9th, yet another Constitutional Amendment Bill (the 41st) was introduced by him in Rajya Sabha. This proposed to give life long criminal immunity to the President, Governors and Prime Minister from all their past deeds as also what ever they do while they hold the office. This was unheard of. It was shocking. It was outrageous. But the Rajya Sabha, reduced now to Mrs. Gandhi’s rubber stamp only, put its unanimous approved it, without any compunction.

This was the monsoon session of Parliament in 1975; but can only be remembered as hurricane session which wrought nothing but havoc. It sought to unabashedly uproot every vestige of parliamentary decency just to save election and authority of one single person- Indira Gandhi.

As chance would have it, however, being last working day, this 41st amendment bill could not be brought to Lok Sabha that session and later on was not pursued and was allowed to lapse. It sank in the dustbin of parliamentary history.

Came the hearing date, August 11th. CJI Justice A N Ray constituted the five judges constitution bench for hearing the appeal. In the light of the amendments, Shanti Bhushan, was virtually left with nothing to argue in appeal; unless, of course, he raised challenge to those amendments first and got it set aside. Now, Mrs. Gandhi was represented by Ashok Sen, the former Law Minister in Nehru’s cabinet. He submitted that amendments were carried out by the Parliament to avoid embarrassment to the judiciary in deciding a question which, according to him, the judiciary was unnecessarily dragged to. He requested for disposal of the appeals in terms of amendments. Shanti Bhushan opposed and, instead, requested to adjourn the case so that a proper challenge to the amendments may be made by filing necessary pleadings first and the appeals may be heard thereafter. CJI was not pleased with the request. He said he wanted to decide expeditiously. He, however, willy nilly adjourned the case for two weeks to August 25th.

Pleadings, thereafter, were completed. Challenge to the 39th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1975 as also to both the amending Acts of 1974 & 1975 to the Representation of the People Act were formally made.

Two weeks period flew by. They were hectic of the lawyers involved. The Basic Structure Doctrine which was firmly established in Keshvananda Bharati case came back to haunt the amendments – with a vengeance. The plea of against the amendments was that it violated the said Doctrine and hence deserved no countenance. This was perhaps for the first time that a constitutional amendment act was being challenged on the ground of hardly two years old BSD. We may recall, the Keshvananda Bharati verdict had come while the election petition was still pending in High Court. They crossed each others path.

The Bench which was constituted to hear the appeal comprised of CJI Ray, Justices Khanna, Mathew, Beg and Chandrachud. They were the five senior most Judges of Supreme Court. Apart from Shanti Bhushan for the petitioner-Raj Narain, Attorney General Niren De and Solicitor General Lal Narain Sinha appeared for Central Govt. to defend the amendments. Ashok Sen and Jagannath Kaushal represented Indira Gandhi.

The hearing eventually started the August 25th. Shanti Bhushan realized that of the five Judges of the Bench, four had held in Keshvananda Bharati that Parliament had uncanalised power to amend the Constitution. Only Justice Khanna had held otherwise. He, as counsel, had a formidable task ahead, then.

Arguments were first made on the constitutional amendments and then election laws amendments. Individual merits of the appeal was not addressed as the understanding was that merit would required to be seen only after it is first ruled by the Court that it had jurisdiction to hear it by deciding the question of amendments. Hearing concluded on October 9th. It had continued for thirty one days.

Then came the day of judgment, after nearly one month – November 7th . All five Judges gave their separate judgments {reported in (1975) Supp SCC 1}. Four Judges reached the same conclusions by same process of reasoning. They struck down the constitutional amendment, upheld the election law amendments and thus validated the election of Mrs Gandhi. The High Court’s judgment stood reversed. It was Justice Beg who decided differently. He chose not to pronounce on constitutional amendment, though he upheld the election laws amendment. And then he did what the rest refrained from doing. He decided the appeal on merits. It surprised the other Judges on the Bench also. He proceeded to absolve Mrs. Gandhi of all the blames. Election of Indira Gandhi, as per Beg’s judgement, stood validated on facts too. But, this again is not the end of surprises in the story. Dispute of election may have ended but not the story of “the” election petition.

Shanti Bhushan was furious to the decision of Justice Beg. After all, merits of the case were not touched during hearing as first the issue was amendments was agreed to be decided by the Court. He sought review on this score.

The Bench did assemble again to hear the review application. It was December 18th. However, nothing came of it. Justice Beg stuck to his position. The review was dismissed by an order pronounced on December 19th. What, of course, came of it was that Justice Beg reflected in poor light. He passed detailed order, to which other Judges did not subscribe. The final order passed by all five Judges only said that since one of them (Justice Beg) was of the opinion that review did not have sufficient grounds, it was dismissed. Justice Khanna later on recollected this as a black day in the history of the Court. It left a sour taste in the mouths of Bar and Bench.

Thus came to climax, story of “the” election petition- the most sensational episode in the saga of Emergency.

Democratic polity of the country never remained the same, thereafter. The citizenry too learned its lesson hard and matured quickly enough. Congress was decimated in the next election in March 1977. Indira Gandhi herself lost the Rae Bareli Lok Sabha constituency to Raj Narain. The next govt. which came to power righted many of the wrongs wrought during Emergency.

One positive outcome, one may perhaps draw, is that Emergency removed the easy complacence of the citizenry and forever endeared to them the democratic freedom and the rule of law. This write up is also an attempt to that realization.

(Write up is entirely based on the inputs from Shanti Bhushan’s Courting Destiny, Prashant Bhushan’s The Case That Shook India, P Krishnaswamy’s V R Krishna Iyer- A Living Legend, H R Khanna’s Neither Roses Nor Thorns, Former Director, Intelligence Bureau, T V Rajeshwar’s India: the Crucial Years and M V Kamath’s Nani Palkhivala- A life)

Authors:

S.M.Singh Royekwar (Advocate- Allahabad High Court at Lucknow)

Sumeet Tahilramani (Advocate- Allahabad High Court at Lucknow)