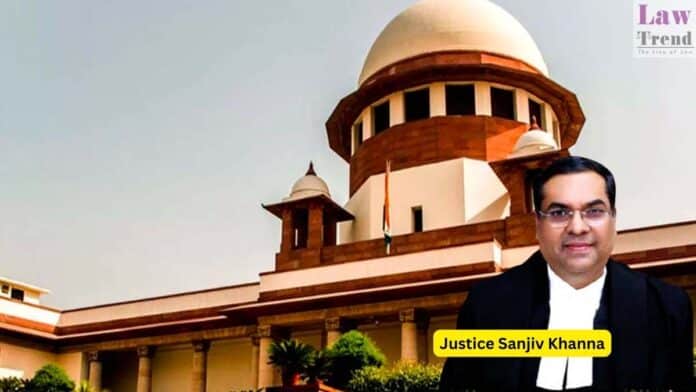

Supreme Court judge Justice Sanjiv Khanna said on Saturday the features of a good law like the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) included its practicality, certainty, consistency in implementation along with its evolution to meet the changing demands of society.

Justice Khanna, who is next in line to become the Chief Justice of India after incumbent DY Chandrachud, speaking at a book launch event, underlined the reasons for the good results shown by the IBC as compared to the earlier company laws.

The third senior-most judge, however, flagged “warning signals” in the IBC which one should look out for.

He said, “Laws are in fact meant to resolve disputes and not become disputed themselves. Laws are not written and meant for legal experts. It is their inherent nature that laws concern everyone and are applicable to almost everything in our daily lives and thus, they must never be a mystery to the ordinary people.”

The scenario was, however, different when it came to commercial and economic laws, as they required “interpretative skills” and were accepted to be “complex”.

“One of the reasons for this is that commercial laws are wide and cover several areas, such as contract, sales, corporate governance, consumer protection, tax, banking and finance,” Justice Khanna said.

So it was difficult to create a comprehensive codification that adequately and accurately reflected all aspects subsumed in a commercial law, he said, adding for assessment and remedies at the pre-default or risk stage, Artificial Intelligence may play a greater role for examination or finding assessment of stress signals for potential insolvency.

The top court judge said, “Further, these laws are constantly evolving with changes in business practices, developments and technological developments. There is also a need to correct anomalies and re-balance competing interests.”

Regarding the general principles of a good law, he said it first needed to be practical and pragmatic to be workable.

The second aspect of a good law is to ensure compliance was a certainty, which was linked to the language of the law, and that required it to be “plain and clear”, he said.

“The third aspect is somewhat contradictory. There must be continuity and consistency in implementation, yet at the same time, the laws must evolve to meet the demands of society,” Justice Khanna said.

He said training of the stakeholders and the handbook that was released for ready reference by the regulator contributed to the strengthening and good results of the IBC.

“Another aspect of the IBC is the approach adopted by the legislature in crafting, recrafting, modelling and updating the laws. The spate of amendments that have taken place to rectify flaws and iron out creases is amazing,” Justice Khanna said.

Highlighting the earlier position in the country, he said between 1987 and 2000, out of 3,068 cases (on an average of 230 cases in a year), the resolution pacts that were approved and the companies that were revived were only 264, which meant an average of 20 cases a year.

“These were worrisome signs. In comparison, IBC has rescued about 2,622 corporate debtors out of which 720 are through resolution plans, 1005 are through appeals, review and settlements and 897 are through withdrawals,” Justice Khanna said.

Referring to certain “warning signs”, in the new law, he said between October and December 2017, the financial creditors under resolution plans were able to realise almost 73 per cent of their claims. But the figures came down slightly between January and March 2019 to 70 per cent.

Justice Khanna said there was, however, a subsequent decline, and from July to September 2020, the figure was a mere 20 per cent.

But unlike the earlier laws such as the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, there are “signs of recovery”, and “for the last two quarters of 2023, the claim is averaging around 30 per cent,” he said.

Justice Khanna said the areas requiring examination in the IBC included the assessment and remedies at the pre-default stage or risk stage and there was also a need for a pre-default debt recovery mechanism and debt restructuring options.

He said there was also the need to examine the inclusion of special situation funds to deal with the bad debt problem.

Justice Khanna also spoke about corporate governance, level of probity and work ethics.

“I would like to see a time when the law of personal guarantors in India is based upon changes from the fairly conservative approach, which is adverse to taking risks in the market economy,” he said.

Also Read

“Personal guarantee in some cases results in denial of access to capital. Personal guarantees are appropriate in certain lending or contractual situations. They are not conducive to the functioning of investment markets. Instead, investment markets rely upon legal structures, regulatory oversight and risk-management practices,” he added.

He said the concept of due diligence did not exist in the country, be it at the level of the banking and financial sector or the corporates.

“I have sat on the company side (designated courts in the high court to deal with company matters). I have seen due diligence reports, including valuation reports which were completely shallow. They were not just dealing with the issues.”

Justice Ramalingam Sudhakar, President of the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and Justice Ashok Bhushan, Chairperson of the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) also spoke at the function.

The dignitaries released the book titled ‘Demystifying the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016’ written by Anant Merathia.