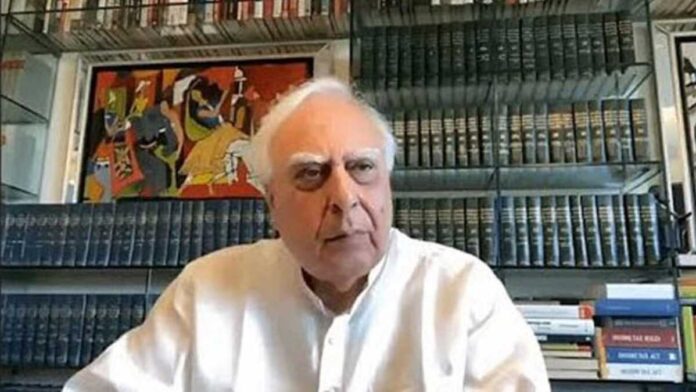

October 26, 2024 – Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal, who currently presides over the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA), delivered a captivating lecture at the Sikkim Judicial Academy. Renowned for his legal acumen and extensive experience, Sibal addressed fundamental issues concerning judicial independence, constitutional principles, and systemic reforms. From his opening statement to the conclusion, Sibal’s address was both a critical analysis and a clarion call for meaningful reforms within the Indian judiciary.

“Speaking as a Citizen, Not as SCBA President”

Sibal began his address by emphasizing that he was speaking as a concerned citizen, rather than in his official capacity as SCBA President. “Ultimately, the goal is to uphold democracy,” he declared, setting the tone for a speech that underscored both the principles of law and its real-world implications. His central thesis revolved around the idea that the law does not inherently equate to justice, and structural reforms are needed to align the judiciary with democratic ideals.

Subordinate Judiciary: A Misnomer

Sibal took issue with the term “subordinate judiciary,” labeling it a misnomer. He explained that while the Constitution uses this term under the chapter on subordinate courts, the judiciary itself is not subordinate in nature. Drawing from historical context, he noted that the Simon Commission’s recommendations in colonial India underscored the importance of competent and just judges to instill public confidence—a concept he deemed vital even today.

He argued that the true test of any judiciary lies in public trust. “If people lack confidence in the judiciary, it undermines its effectiveness,” Sibal warned, linking this concern to broader discussions about judicial appointments and accountability.

Historical Evolution of Judicial Appointments

Tracing the evolution of judicial appointments, Sibal recalled the 1934 Joint Select Committee’s recommendations, which aimed to ensure independence from governmental influence. He detailed how the Government of India Act, 1935, shaped the structure of district-level judicial appointments, emphasizing the role of governors and High Courts.

Sibal highlighted how subsequent judicial conferences in 1948 recognized the need for greater High Court control over appointments to ensure judicial autonomy. This led to Article 235 of the Indian Constitution, which placed civil judiciary appointments under High Court oversight. However, he critiqued the prevailing system for failing to deliver complete independence, noting that High Courts still exercise significant control over district judges, often leading to allegations of bias and unfair promotions.

The Collegium System and Its Shortcomings

The lecture then turned to the controversial collegium system, responsible for judicial appointments to the Supreme Court and High Courts. Sibal acknowledged his past advocacy for the collegium system, but he criticized its current execution. “It was intended to protect judicial independence, but it has become centralized and arbitrary,” he asserted.

Sibal pointed out that High Court judges often seek favor from Supreme Court judges to be considered for elevation. This dynamic, he argued, compromises the integrity of appointments, as merit can sometimes take a backseat to networking and favoritism. He called for clearer criteria in appointments, stressing that the process should be more transparent and meritocratic.

Bail and Precedent: Realities on the Ground

Delving into substantive legal issues, Sibal critiqued the application of the “bail as the rule, jail as the exception” principle. He argued that subordinate courts often deny bail due to fear of backlash from higher authorities, leading to a culture of judicial conformity rather than independent decision-making.

The speech also touched on the erosion of the stare decisis principle, which historically provided predictability through precedent. According to Sibal, the rise of statute-driven law, exemplified by the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), has created uncertainty in judicial rulings. He cited cases where statutory interpretations have undermined established precedents, such as the 50% reservation cap, resulting in a legal landscape marked by inconsistency.

Sibal’s Take on PMLA and Article 21

Sibal was particularly critical of the PMLA, a law he described as both substantively and procedurally unreasonable. He outlined how the twin-test for bail under the PMLA places an undue burden on the accused, contravening the constitutional mandate of “procedure established by law” under Article 21.

Sibal pointed to the recent Supreme Court judgment in the Pankaj Bansal case, which recognized the need for written grounds for arrest to uphold individual rights. He argued that the Supreme Court should continue to carve out exceptions grounded in Article 21, to provide relief where procedural law fails to deliver justice.

Institutional Reforms: Need for a Fresh Approach

The lecture culminated in a broader call for institutional reforms. Sibal contended that judicial independence cannot be fully realized under the current system of centralized control, whether by the High Courts or the collegium. He proposed moving toward a more inclusive and decentralized system that incorporates diverse viewpoints and emphasizes public confidence in the judiciary.

He also suggested that India rethink colonial-era laws and practices, such as police remand, which he characterized as antithetical to modern democratic principles. “In developed countries, investigations precede arrests, while here, arrests precede investigations,” he observed, underscoring the urgent need for reforms that align with global best practices.

A Candid Critique of Judicial Accountability

Sibal’s address was as much a critique of the judiciary’s inner workings as it was a reflection on India’s democratic evolution. His candid analysis, drawn from over five decades of legal practice, offered a rare insider’s perspective on the challenges and shortcomings of the Indian judicial system.

As the lecture concluded, it was clear that Sibal’s message extended beyond the walls of the Sikkim Judicial Academy. His call for judicial reforms, transparency, and genuine independence is likely to resonate across legal circles and spur discussions on the future trajectory of India’s judiciary.