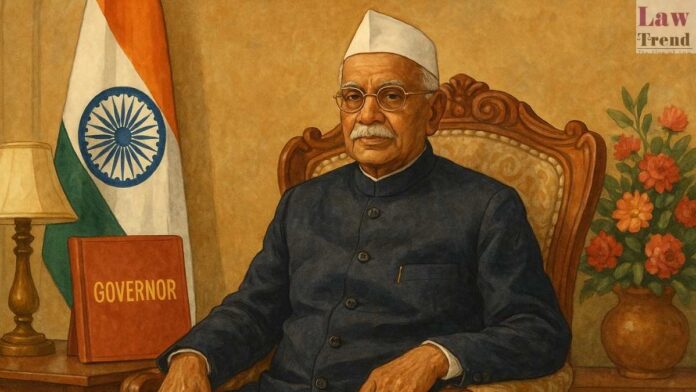

The office of the Governor is a cornerstone of the Indian federal structure, designed to be a vital link between the Union and the States. Yet, few constitutional posts have been as consistently mired in controversy. The central question that has animated political and legal discourse for decades is whether the Governor functions as an impartial constitutional guardian of the state or as a political agent of the central government that appoints them. This tension is not a matter of opinion or bias; it is embedded in the very constitutional framework that defines the Governor’s dual and often conflicting responsibilities.

The Constitutional Mandate: A Duality of Roles

The Constitution of India outlines the Governor’s position through several key articles. Article 153 provides for a Governor for each state, and Article 154 vests the executive power of the state in them. The Governor is appointed by the President (Article 155) and holds office “during the pleasure of the President” (Article 156), which in practice means the pleasure of the Union government.

On one hand, the Governor is the constitutional head of the state. Article 163 stipulates that there shall be a Council of Ministers with the Chief Minister as its head to “aid and advise the Governor” in the exercise of their functions. In this capacity, the Governor is expected to act as a nominal head, much like the President of India, bound by the advice of the elected state government. Their functions include appointing the Chief Minister and other ministers (Article 164), summoning and dissolving the state legislature (Article 174), and giving assent to bills (Article 200).

On the other hand, the Constitution carves out a crucial exception in Article 163, stating that the Governor is not bound by the aid and advice of the ministers for functions that the Constitution requires them to perform in their “discretion.” It is this discretionary space, combined with the power of appointment and removal resting with the Centre, that creates the Governor’s second role: that of a representative and agent of the Union government.

The Flashpoints of Controversy

The friction between these two roles becomes most apparent in specific situations where the Governor’s discretionary powers are exercised.

- Appointment of the Chief Minister: In the event of a fractured electoral verdict with no single party or pre-poll alliance securing a majority, the Governor’s discretion to decide who to invite to form the government comes into play. This decision has frequently been criticized for being politically motivated, with Governors often accused of inviting parties aligned with the ruling party at the Centre, even if they lacked a clear claim to a majority.

- Recommending President’s Rule (Article 356): The Governor has the power to send a report to the President if they are satisfied that “a situation has arisen in which the government of the State cannot be carried on in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution.” This report can form the basis for the imposition of President’s Rule. Historically, this has been the most contentious power. Data shows that Article 356 has been used over 100 times, often on grounds that have been challenged as partisan and aimed at destabilizing or dismissing state governments led by opposition parties.

- Reserving Bills for Presidential Consideration: Under Article 200, the Governor can reserve a bill passed by the state legislature for the consideration of the President. While intended as a safeguard against unconstitutional legislation, this power has been used to delay or veto legislation passed by state governments, particularly when the state and central governments are ruled by different parties. This has led to standoffs and accusations that Governors are obstructing the will of the elected state legislature at the behest of the Centre.

Judicial Intervention and Constitutional Guardrails

The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, has repeatedly stepped in to clarify the limits of the Governor’s powers and reinforce their role as a constitutional guardian.

- In Shamsher Singh vs. State of Punjab (1974), the Court held that the President and Governor are constitutional heads and must act on the aid and advice of their Council of Ministers, except where a constitutional provision expressly requires them to act in their discretion.

- The most definitive pronouncement came in the landmark S.R. Bommai vs. Union of India (1994) case. The Supreme Court laid down stringent guidelines to prevent the misuse of Article 356. It ruled that the test of a government’s majority must be conducted on the floor of the Legislative Assembly, not in the subjective opinion of the Governor. The judgment established that a proclamation imposing President’s Rule is subject to judicial review, thereby holding the Governor’s report and the President’s satisfaction accountable.

- More recently, in Nabam Rebia vs. Deputy Speaker (2016), the Supreme Court further circumscribed the Governor’s discretionary powers, holding that a Governor cannot act to summon or dissolve the assembly in a manner that undermines an elected government.

The Unfinished Agenda of Reform

Recognizing the persistent friction, several high-level commissions have recommended reforms to insulate the Governor’s office from political pressures.

- The Sarkaria Commission on Centre-State Relations (1988) recommended that the Governor should be an eminent person from outside the state, should not have taken part in active politics recently, and that the state’s Chief Minister must be consulted before their appointment. It stressed that Article 356 should be used “very sparingly, in extreme cases, as a measure of last resort.”

- The Punchhi Commission on Centre-State Relations (2010) reiterated many of these suggestions and went further. It proposed a fixed five-year tenure for Governors and recommended that they should be removed only through a resolution passed by the state legislature, not at the “pleasure” of the President. It also provided a clear order of precedence for the Governor to follow when inviting a party to form a government after an election.

Conclusion: A Structural Dilemma

The debate over the Governor’s role is not merely about the conduct of individuals but about a fundamental structural dilemma within the Indian Constitution. The office was conceived as a linchpin to ensure constitutional governance within states while preserving the unity and integrity of the nation. However, the mechanism of appointment and removal, coupled with vaguely defined discretionary powers, has made the office susceptible to political manipulation.

While the Supreme Court has erected significant legal barriers against the arbitrary exercise of power, the potential for friction remains. The ultimate resolution lies not just in legal or constitutional amendments but in the cultivation of a political culture where the central government exercises restraint and the incumbents in Raj Bhavans prioritize their oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution” above all else. Until then, the office of the Governor will continue to be a contested space, caught between its two constitutional masters: the state legislature to which it is nominally accountable, and the central government to which it owes its existence.

Byline: Sourabh Yadav

Disclaimer: The views expressed are the author’s personal opinions.