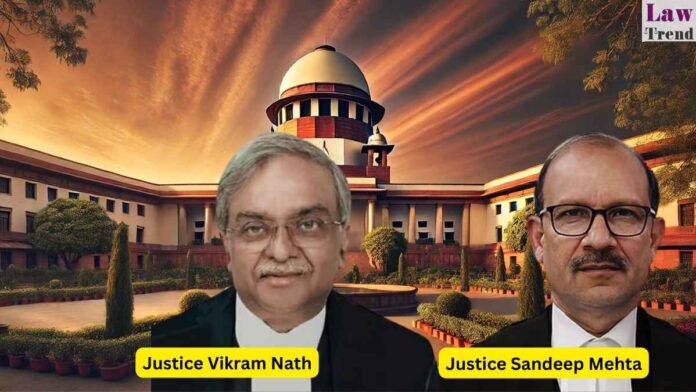

In a landmark judgment addressing the escalating crisis of student suicides, the Supreme Court of India has transferred the investigation into the unnatural death of a 17-year-old NEET aspirant to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and issued a comprehensive set of interim guidelines to safeguard the mental health of students in all educational institutions

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.