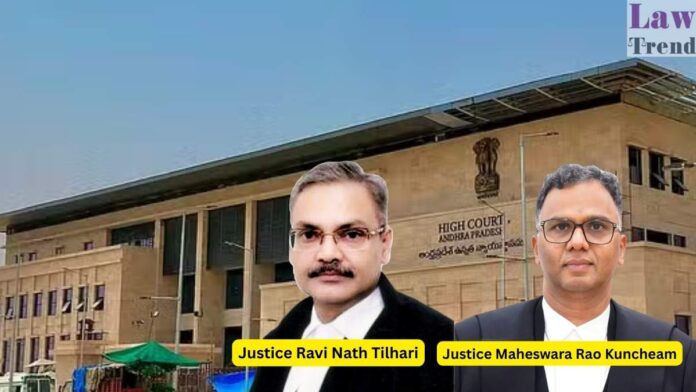

In a significant ruling with wide-ranging implications for land dispute litigation, the Andhra Pradesh High Court has held that appeals against the orders of Special Tribunals under the Andhra Pradesh Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act, 1982, are not maintainable before the High Court. A division bench, comprising Justice Ravi Nath Tilhari and Justice Maheswara Rao Kuncheam,

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.