The authority conferred upon investigating officers (IOs) in the course of a criminal investigation is sometimes misconstrued as absolute, leading to an unfortunate propensity for overstepping. The practice of IOs drafting statements under Section 161 CrPC to buttress their own theory of the case, rather than objectively recording the accused’s account, can have far-reaching consequences, often resulting in a profound failure of justice. The said section , now in an amended form , under section 180 of BNSS reads as follows :-

“Examination of witnesses by police.

180. (1) Any police officer making an investigation under this Chapter, or any police officer not below such rank as the State Government may, by general or special order, prescribe in this behalf, acting on the requisition of such officer, may examine orally any person supposed to be acquainted with the facts and circumstances of the case.

(2) Such person shall be bound to answer truly all questions relating to such case put to him by such officer, other than questions the answers to which would have a tendency to expose him to a criminal charge or to a penalty or forfeiture.

(3) The police officer may reduce into writing any statement made to him in the course of an examination under this section; and if he does so, he shall make a separate and true record of the statement of each such person whose statement he records:

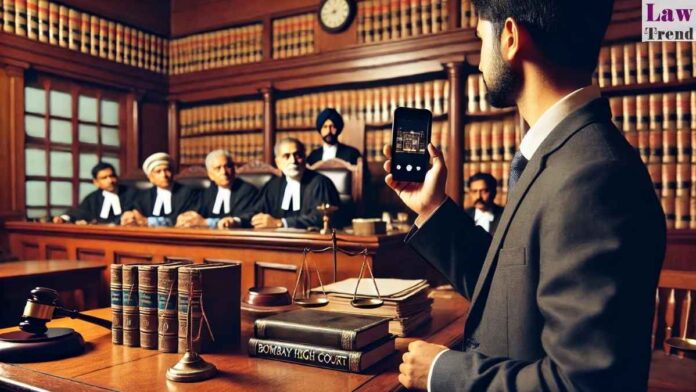

Provided that statement made under this sub-section may also be recorded by audio-video electronic means:

Provided further that the statement of a woman against whom an offence under section 64, section 65, section 66, section 67, section 68, section 69, section 70, section 71, section 74, section 75, section 76, section 77, section 78, section 79 or section 124 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 is alleged to have been committed or attempted, shall be recorded, by a woman police officer or any woman officer.”

The requirement of recording statements through ‘audio-video electronic means‘ is not inherently sacrosanct and is susceptible to manipulation. Moreover, such statements must conform to the statutory prescriptions outlined in Section 23 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, ensuring their admissibility and reliability in legal proceedings.

The crux of the matter lies in the admissibility and utilization of statements and information provided by accused and victims to investigating officers and supervisory authorities through electronic means, including emails and messaging platforms like WhatsApp. As law enforcement leverages these mediums to track offenders and build cases, it is imperative to incorporate them as evidence, subject to compliance with statutory requirements under the Information Technology Act, Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, and Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam. This clarity will safeguard individuals from harassment and victimization by disgruntled informants who attempt to convert civil disputes into criminal prosecutions, a practice repeatedly deprecated by the Supreme Court, as seen in Rikhab Birani v. State of U.P. (SLP(Crl) No. 8592/2024) and numerous cases involving false accusations in matrimonial disputes with ulterior motives. These cases encompass a disturbing trend of false prosecutions, including matrimonial disputes where families and friends are entangled in criminal proceedings, civil property matters being criminalized, and commercial disputes being transformed into criminal cases. The latter, a relatively recent phenomenon, often involves rival businessmen and employer-employee conflicts, resulting in a grave miscarriage of justice.

Effective investigation in such cases hinges on the police officer’s willingness to consider evidence and statements provided by the accused. However, requests to incorporate such material are often met with refusal. When the accused attempts to follow up on their submissions via email, online portals, or RTI applications, seeking acknowledgment of receipt, responses are frequently evasive or formulaic, citing “peshbandi” without substantive engagement. Furthermore, such correspondences are often excluded from case diaries, contravening the Supreme Court’s directive in Sharif Ahmad v. State of UP, reported in 2024 INSC 363 which underscores the importance of transparency and accountability in investigation.

The significance of information provided to investigating officers and superior officers via electronic modes, such as email, WhatsApp, IGRS (Integrated Grievance Redressal System of Uttar Pradesh Government, wherein an applicant can have recourse to the decision makers , by providing his applications and evidence which have to be considered by the officer concerned and to be reverted within a stipulated time frame) , raises a crucial question: must such communications be incorporated into the investigation? In this context, the Supreme Court’s judgment in Zakia Ahsan Jafri v. State of Gujarat (2022) 6 SCR 1 is noteworthy. Specifically, paragraph 63 of the judgment highlights the importance of considering all relevant material, including communications, in the investigation process :-

“63. Needless to underscore that every information coming to the investigating agency must be regarded as relevant. However, the investigating agency is expected to make enquiries regarding the authenticity of such information and after doing so must collect corroborative evidence in support thereof. In absence of corroborative evidence, it would be merely a case of suspicion and not pass the muster of grave suspicion, which is the pre-requisite for sending the suspect for trial. This is the mandate in Section 173(2)(i)(d) of the Code, which postulates that the investigating officer in his report must indicate whether any offence appears to have been committed and if so, by whom. The opinion of the investigating officer formed on the basis of materials collected during the investigation/enquiry must be given due weightage. That would only be the threshold, to facilitate the concerned Court to take cognizance of the crime and then frame charge if it is of the opinion that there is ground for presuming that the accused has committed an offence triable under Chapter XIX of the Code.”

In consonance with the sacrosanct principles enunciated by the judiciary, it is imperative that all information furnished to investigating officers and superior authorities through electronic modes be meticulously documented and incorporated into the case diary. The Investigating officer, in any case, shall be within his rights to examine the evidence so provided and may require the person providing the information to prove / corroborate it , and may summon him or record his statement, for which electronic mode may also be put to use, to enable those who live far away cooperate in investigation.

This imperative assumes paramount importance, for it is only through such diligent and exhaustive recording that the twin objectives of a fair and thorough investigation can be meaningfully achieved. By embracing this approach, the accused is afforded a precious opportunity to be heard, thereby safeguarding the innocent from unwarranted victimization and ensuring that the majestic ends of justice are met with utmost precision and rectitude. In the interests of upholding the rule of law and preventing egregious miscarriages of justice, urgent action is necessitated to instil this protocol into the investigative fabric, lest the guilty go unpunished and the innocent suffer irreparable harm.

Article by: SM Haider Rizvi

Advocate High Court- Lucknow

myvakil@gmail.com