In a noteworthy ruling, the Calcutta High Court has quashed criminal proceedings against a customer implicated under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act of 1956. The court determined that the individual’s role as a customer did not satisfy the criteria for prosecution under the Act, as there was no evidence of involvement in the management or

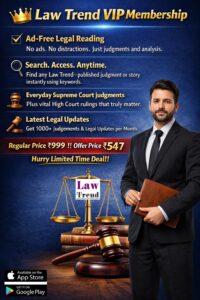

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.