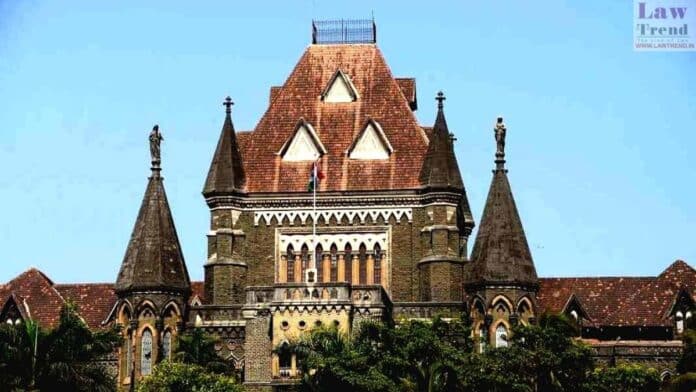

The Bombay High Court has ruled that a flat under construction, which has not yet been handed over or occupied by either party, does not fall within the definition of a “shared household” under Section 2(s) of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. The Court dismissed a writ petition seeking a direction

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.