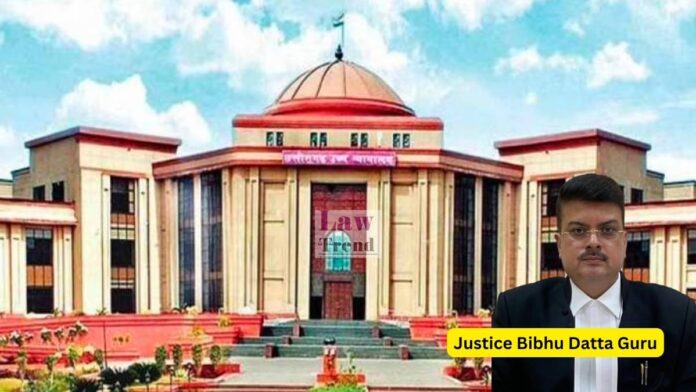

In a landmark decision, the Chhattisgarh High Court quashed the royalty imposition on “Vanadium Sludge,” ruling that it does not qualify as a mineral under the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957. Justice Bibhu Datta Guru delivered the judgment in the case Bharat Aluminium Company Limited vs. State of Chhattisgarh & Ors., (WP(C)

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.