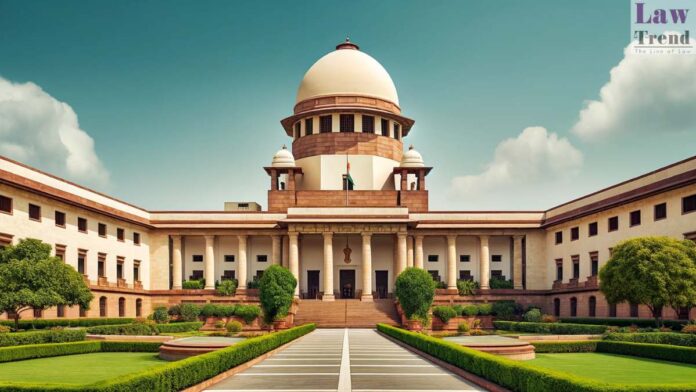

The Supreme Court of India has delivered a significant judgment clarifying the relationship between procedural remedies and inherent judicial powers. The Court held that the availability of an alternative remedy under Section 397 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) cannot alone be a valid reason to dismiss an application filed under Section 482 CrPC.

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.