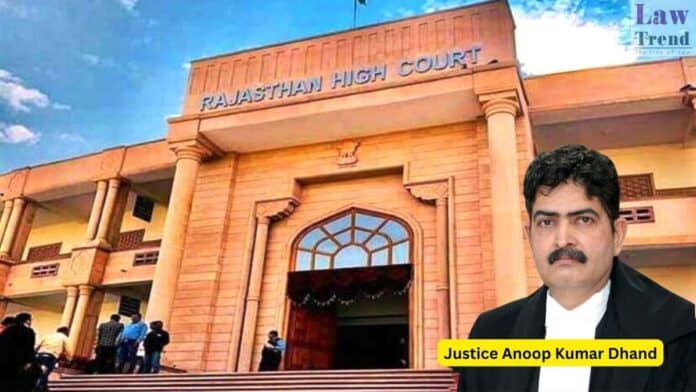

The Rajasthan High Court, in a recent judgment, has reaffirmed a crucial principle of contract law, holding that a power of attorney automatically terminates upon the death of the principal. Consequently, any sale of property executed by the power of attorney holder after the principal’s demise is void. Justice Anoop Kumar Dhand dismissed a writ

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.