The Supreme Court has ruled that a party who takes possession of property during the pendency of litigation, with full knowledge of the dispute, cannot claim protection under Section 53A of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. The judgment came in Civil Appeal No. 3616 of 2024, where appellant Raju Naidu’s claim over a property

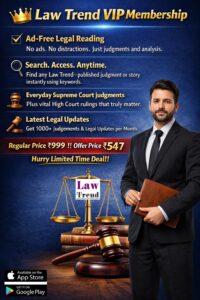

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.