The Supreme Court of India has held that contractual stipulations purporting to bar claims for regularization cannot override constitutional guarantees, and the State, as a model employer, cannot rely on contractual labels to discard long-serving employees in a manner inconsistent with fairness and dignity.

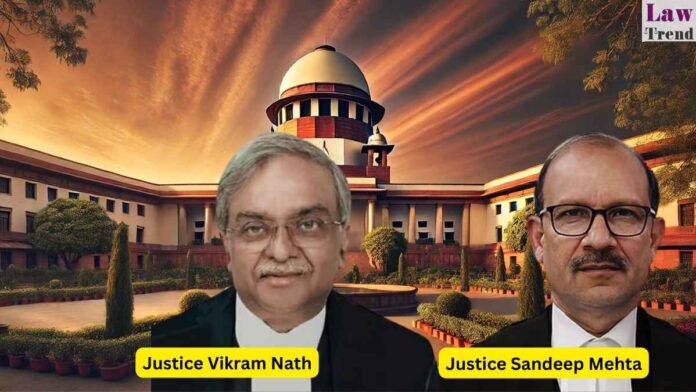

A Bench comprising Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta set aside the judgments of the Jharkhand High Court which had declined to regularize the services of Junior Engineers (Agriculture) appointed on a contractual basis. The Apex Court directed the State of Jharkhand to “forthwith regularize the services” of the appellants against the sanctioned posts to which they were initially appointed.

Background of the Case

The appellants were appointed pursuant to an advertisement issued in September 2012 for 22 sanctioned posts of Junior Engineers (Agriculture) in the Land Conservation Directorate. The appointment letters stipulated that the engagement was temporary and on a contractual basis for an initial period of one year, extendable subject to satisfactory performance. The terms also stated that the State would not be liable to regularize the appointees.

The appellants continued in service through periodic extensions for over a decade. In 2015, the Director of Soil Conservation forwarded a representation to the State Government proposing the framing of rules for their regularization. However, in February 2023, the appellants were granted what they apprehended was a final extension, leading them to approach the High Court.

They sought a writ of mandamus for regularization, invoking the State’s obligation to act as a model employer. The Single Judge of the Jharkhand High Court dismissed the writ petitions on May 14, 2024, holding that the appellants possessed no legal right to seek renewal or regularization given the contractual nature of their engagement. Subsequent intra-court appeals were also dismissed by the Division Bench, which held that judicial directions could not alter the terms of a bilateral contract.

Arguments Before the Supreme Court

Senior Advocate K. Parameshwar, appearing for the appellants, argued that the appellants were appointed against vacant, sanctioned posts after a due selection process involving roster clearance. He submitted that they had rendered continuous service for over 10 years without any break or adverse record.

Mr. Parameshwar contended that the stipulation in the appointment letters barring regularization was contrary to public policy and hit by Section 23 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, as the appellants, being unemployed job seekers, lacked equal bargaining power. He relied on the Constitution Bench decision in State of Karnataka v. Uma Devi (2006) to argue for regularization and asserted that the State’s refusal violated Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution.

Conversely, the counsel for the State of Jharkhand argued that the appellants had entered into the agreement with full knowledge of the terms, including the express bar on regularization. It was submitted that since the engagement was purely contractual, the appellants acquired no enforceable right to continue in service or seek regularization in the absence of a specific scheme.

Supreme Court’s Analysis and Observations

The Supreme Court expressed disapproval of the High Court’s mechanical application of precedents without engaging with the core constitutional issues. The Bench emphasized that the State is a “model employer” and cannot exploit the vulnerability or unequal bargaining position of its employees.

1. Unequal Bargaining Power: The “Lion and Lamb” Analogy: Referring to the disparity between the State and an individual job seeker, the Court observed:

“The State, in such a relationship, assumes the role of a metaphorical lion, endowed with overwhelming authority, resources and bargaining strength, whereas the employee, who is yet an aspirant, is reduced to the position of a metaphorical lamb, possessing little real negotiating power.”

The Court held that in such structural inequality, Constitutional Courts must tilt in favor of protecting the weaker party. Relying on Central Inland Water Transport Corpn. v. Brojo Nath Ganguly (1986) and Pani Ram v. Union of India (2021), the Bench reiterated that courts will not enforce unfair or unreasonable contracts entered into between parties with unequal bargaining power.

2. No Waiver of Fundamental Rights: Citing Basheshar Nath v. Comm. Income Tax (1958), the Court held that fundamental rights are incapable of waiver. Therefore, the mere fact that the engagement was governed by contractual terms does not amount to a waiver of the appellants’ rights under Article 14 against arbitrary State action.

3. Legitimate Expectation: The Court distinguished the present case from the limitations set in Umadevi. It clarified that the bar against legitimate expectation applies to engagements not preceded by a proper selection process. Since the appellants were appointed against sanctioned posts following a due selection procedure, the Court held they could invoke the doctrine.

“The repeated conduct of the employer-State in expressing confidence in their performance and consistently granting monetary upgrades & tenure extensions reasonably nurtures an expectation that their long and continuous service would receive further recognition,” the Court noted.

4. Arbitrariness and Ad-hocism The Bench termed the State’s decision to discontinue the appellants after nearly ten years as “manifestly arbitrary.” The Court cited Dharam Singh v. State of U.P. (2025) to deprecate the culture of “ad-hocism” and the practice of keeping employees under nominal labels to evade regular employment obligations.

The Decision

The Supreme Court allowed the appeals and set aside the judgments passed by the High Court of Jharkhand. The Court issued the following directions:

- Rejection of Contractual Defence: The Court held that contractual stipulations cannot immunize arbitrary State action from constitutional scrutiny.

- Regularization Ordered: The Respondent-State was directed to “forthwith regularize the services of all the appellants against the sanctioned posts to which they were initially appointed.”

- Benefits: The appellants were held entitled to all consequential service benefits accruing from the date of this judgment.

The Court concluded that the State cannot rely on contractual labels or a mechanical application of Umadevi to justify prolonged ad-hocism.

Case Details:

- Case Title: Bhola Nath v. The State of Jharkhand & Ors. (and connected appeals)

- Case No: Civil Appeal No. of 2026 (Arising out of SLP (Civil) No. 30762 of 2024)

- Coram: Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Sandeep Mehta