The Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court, while refusing to quash a 12-year-old criminal proceeding, has strongly censured both the State Police and the subordinate judiciary for a “12-year stagnation” caused by the repeated failure to serve summons on the accused. In a petition (Crl.OP(MD)No.13075 of 2025) heard by Justice B. Pugalendhi, the Court

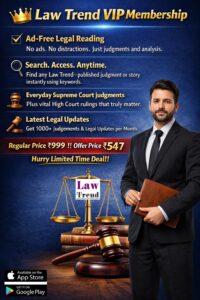

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.