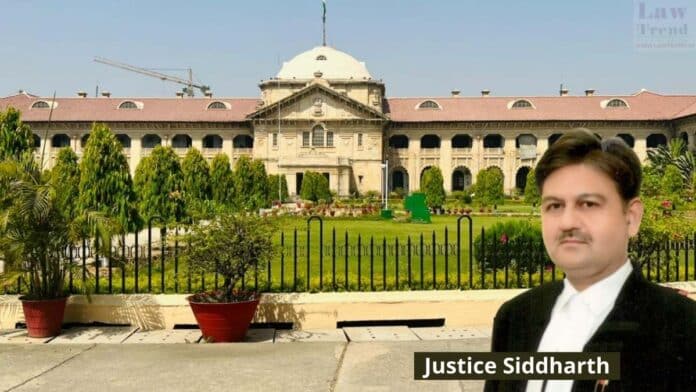

The Allahabad High Court, in a significant ruling, has set aside orders from a Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) and a Children’s Court that directed a 17-year-old to be tried as an adult for heinous offences, including murder. Citing the “arbitrary manner” in which preliminary assessments of juveniles are being conducted, Justice Siddharth has formulated a

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.