The Supreme Court of India, in a significant ruling on arbitration law, has held that the three-month limitation period for filing an application to set aside an arbitral award under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, commences only when a signed copy of the award is delivered to the actual ‘party’ to

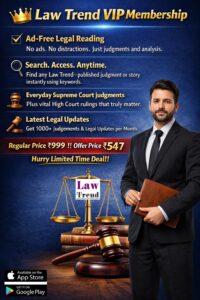

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.