The Supreme Court has ruled that the prosecution is permitted to submit documents or materials that were inadvertently omitted at the time of filing the chargesheet, even if such materials were available prior to that filing. This principle was reaffirmed in Sameer Sandhir v. Central Bureau of Investigation (Criminal Appeal Nos. 4718–4719 of 2024), a

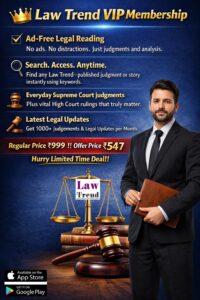

To Read More Please Subscribe to VIP Membership for Unlimited Access to All the Articles, Download Available Copies of Judgments/Order, Acess to Central/State Bare Acts, Advertisement Free Content, Access to More than 4000 Legal Drafts( Readymade Editable Formats of Suits, Petitions, Writs, Legal Notices, Divorce Petitions, 138 Notices, Bail Applications etc.) in Hindi and English.